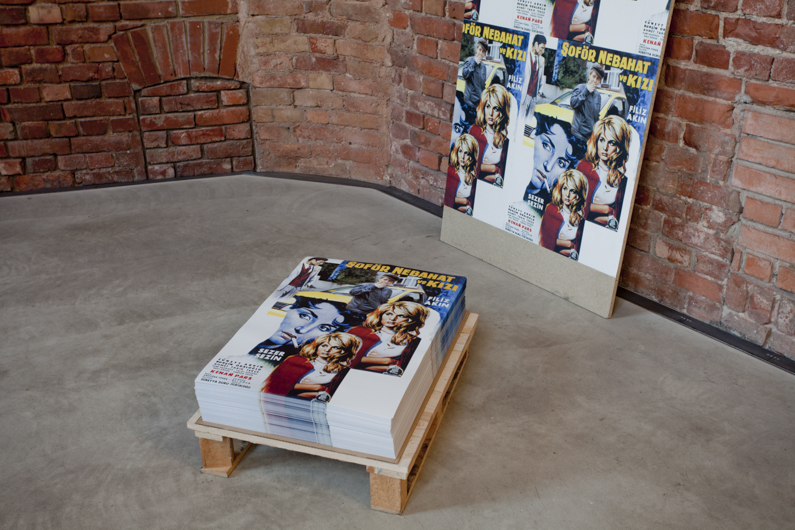

With his video installationNebahats Schwestern(Nebahat’s Sisters),Emanuel Mathias goes in search of a fictive, female film figure in reallife. In so doing, he explores the preliminary image, the copy, andafter-image of such a “character” in a filmic and metaphoric sense,and questions the order of these images, which is generallyconsidered fixed, by way of montage and other methods. Hiscomplex installation, thematically and formally convincing, consistsof a three channel video projection, filmed interview sequences, anda photograph, and oscillates between a remake and a real timemovie, between a live(tableau vivant)and a living image, betweenreportage and role play, and touches on gender and ethnic conflicts.On the one hand,Nebahats Schwesternis based on authenticreports and film scenes acted out by three Turkish women taxidrivers, while at the same time including selected sequences fromthe 1960 filmŞofoÅNr Nebahatand an interview with the mainactress.Şoför Nebahatwas filmed several times or rather in severalinstallments, and these television films from the 1960s and 1970sstill enjoy great popularity in Turkey today. They tell the story of ayoung female taxi driver in the process of emancipating herself;despite working in a profession that is superficially masculine—as isher habitus—she manages to preserves her underlying femininityand masters her life as a woman. Nebahat is thus an actual pre-existing image that is still very present in the media, and one thathardly anyone in Turkey can see past.For Emanuel Mathias, dealing with a motif specific to a country or alocation subject might well have been the natural result of his 2010DAAD fellowship in Istanbul. Yet withNebahats Schwesternhe alsocontinues the visual investigations of gestures and their meanings,both as handed down by tradition and as they shift during culturalhistory, and the construction of visual narratives that alreadyinterested him in his cautiously staged photography. Mathias’ firstfilm work is also formally striking: but now beyond the internalstructures of individual images, this work impresses with itsprofessional editing, which here in particular entails the preciselycoordinated linkage of various image sequences and temporallayers. In so doing, the attentive viewer can easily grasp theaudiovisual, narrative film strands, and the interchange betweendiverse Nebahats never becomes a confusing comedy of errors. Onthe contrary, parallels and interferences among these Nebahatimages are visualized in a very impressive fashion. It is thus possiblefor Mathias to spread out an ambivalent role-play and image ofwomen in which he addresses an almost historical model by way ofits current after images. For the most interesting is the image ofNebahat in those not only filmic gaps that are filled byNebahatsSchwestern,so to speak in terms of reception. This way of“completing an image” or “becoming a real image” is more fascinating than a film hero who steps directly out of the screen andinto the audience, and yet remains on the projection surface. Whenone of the taxi drivers questioned by Emanuel Mathias and histranslator says that she (who has the same name as the film figure!)could play Nebahat by integrating the screenplay into her life, for amoment not only are preliminary image and after image or fictionand reality exchanged, but reality seems to be possible as a film.More still, the artist here reflectsupon the effect that an artificial-artistic image can have on the life ofspectators and art beholders.